Pressure-volume loops in the presence of lung pathology

Pressure-volume loops can inform us about changes in the patient's lung compliance, air leaks, patient-ventilator dyssynchrony, and increased work of breathing. For instance, they may reveal alveolar overdistension, or help determine the optimal level of PEEP (the so-called "critical opening pressure") for a patient with ARDS. A brief summary is offered to the Part II candidate in the Required Reading section for respiratory medicine and mechanical ventilation, as an aide memoir. The CICM Part I exam has never contained any SAQs about any of these issues. The Part I exam candidate can safely omit this section in favour of higher scoring topics.

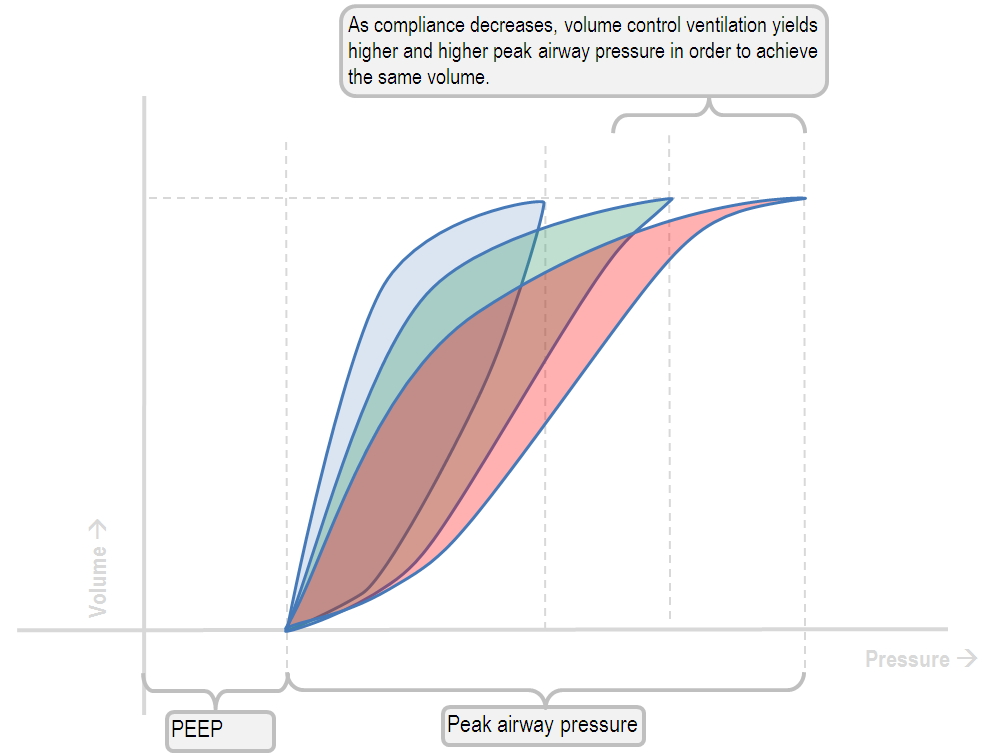

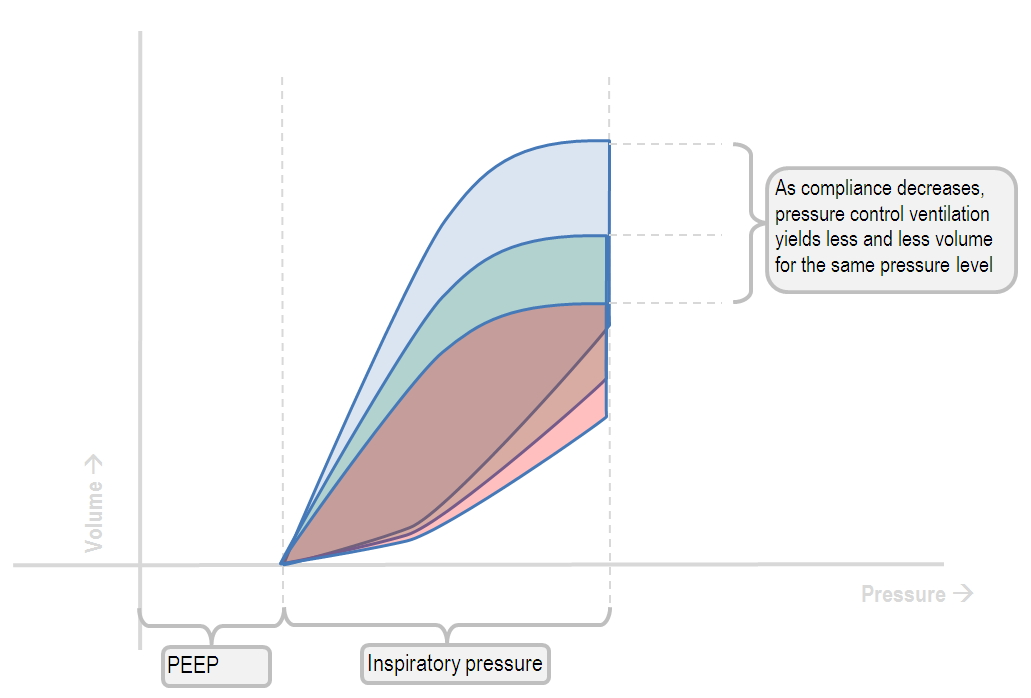

Changes in respiratory compliance, and their influence on the pressure-volume loop

As ones lungs become less and less compliant, a volume-controlled mode will generate increasingly higher peak airway pressures. Ultimately, a "beaked" region will develop, signalling alveolar overdistension.

Conversely, in pressure-control mode, the pressure remains the same, but the volume generated will decrease.

Rather than dangerous alveolar hyperinflation, this strategy results in hypoventilation and hypercapnoea.

A pressure-volume loop with an air leak in the circuit

pressure volume curve with an air leak

One can determine the magnitude of the air leak by where on the volume-coordinate the curve stopped.

This volume of gas has essentially disappeared from the closed circuit.

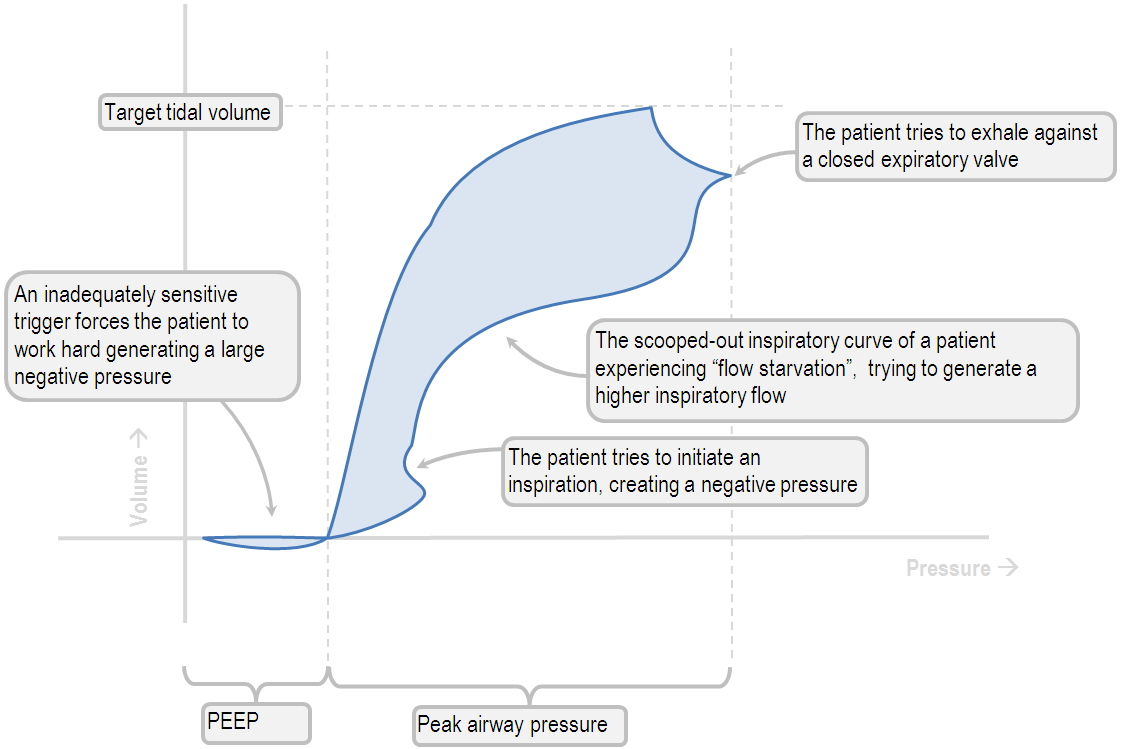

A pressure-volume loop with patient-ventilator dyssynchrony

The above loop has several dyssynchrony problems all demonstrated on one loop. First the trigger is too tight, then the patient tries to initiate another breath mid-inspiration, then the flow is too weak, and then the patient tries to exhale before the ventilator is ready. Its a comedy of errors.

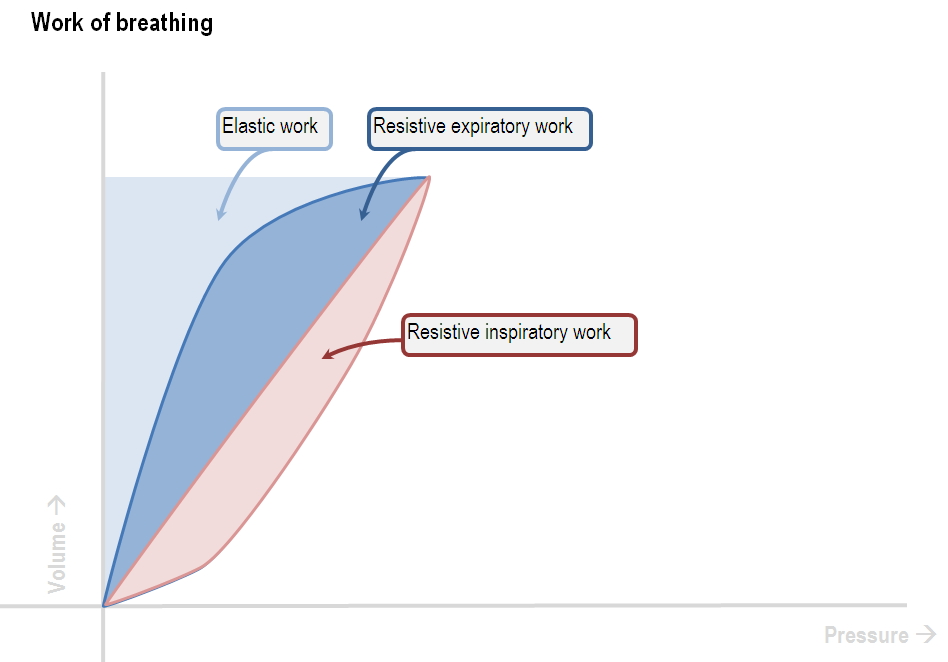

Relationship of pressure and volume to work of breathing

Why, they are closely related. In fact;

Essentially, this means that the area under (or, to the left) of the pressure-volume loop is the work of breathing.

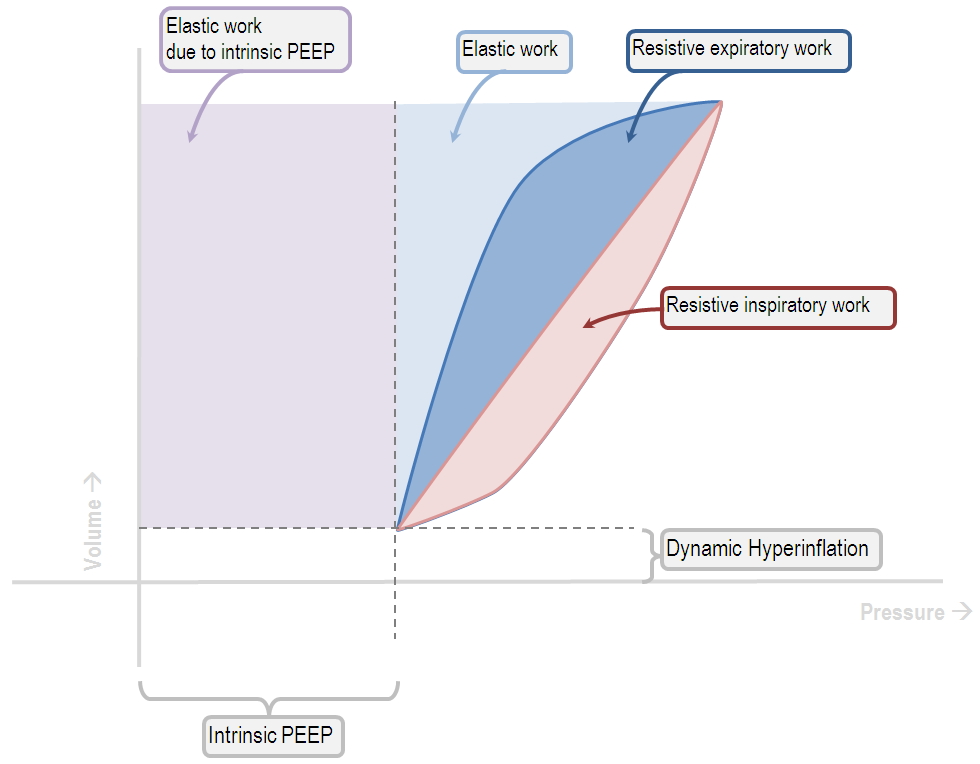

From this it becomes obvious, that anything increasing the convexity of the inspiratory curve, and anything pushing the whole loop to the right, will be increasing the work of breathing.

For instance, witness the work of breathing in the context of severe asthma.

Of course, in this setting the work of breathing is shared between the ventilator and the patient.